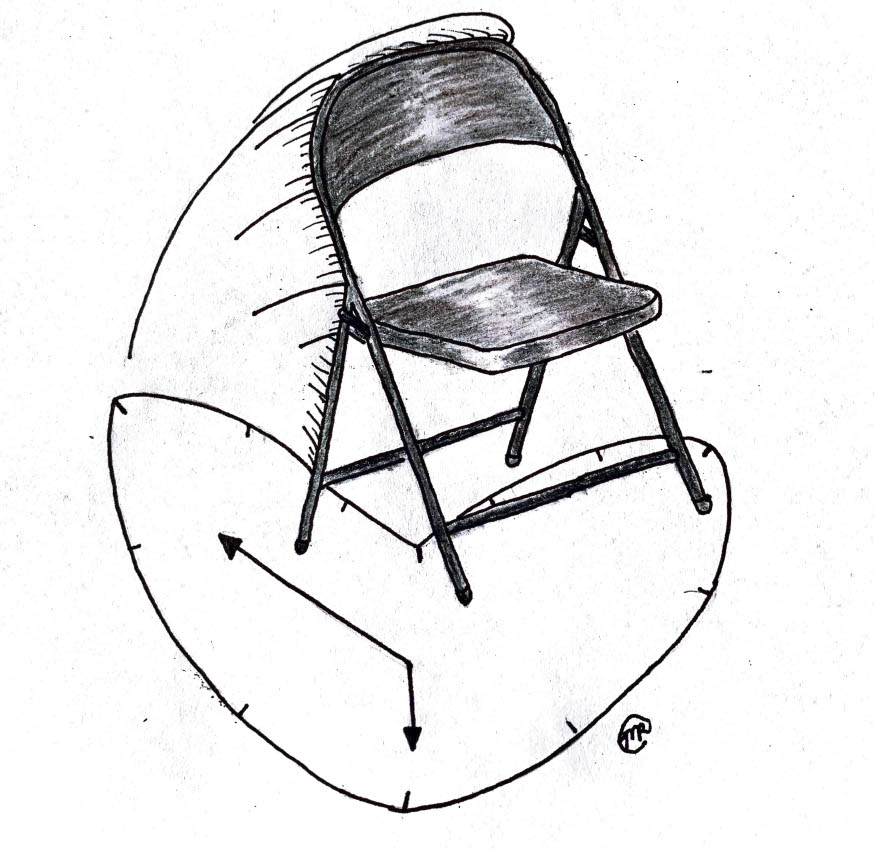

A seat at a table. It’s a foldable chair. The kind that comes in beige or gray. The kind that everyone will help stack on racks at the end of evening.

My partner sits in one. There for an awards banquet for her fire station.

Three other firefighters sit in these chairs. Two with their wives beside them, one with kids also.

All the firefighters wear their navy-blue uniforms. Pressed. Folds stiff like the chairs they occupy.

A dozen tables populate the warehouse-like public space. Chairs surround them.

So many chairs.

The ceremony starts. A pinning takes place to honor veteran firefighters. One firefighter’s wife pins the award to his lapel. Another firefighter does not have a wife to do the honors, so a colleague volunteers. He moves to the makeshift stage.

As he does, one firefighter at my girlfriend’s table shouts: “No homo!”

The laughter spreads around the table. Then around the room, chair by chair.

I am not present for this. I’m not seated in one those uncomfortable chairs. The kind that will impress a line on the back of your thigh if you sit long enough—maybe the length of a ceremony. I’ve heard enough stories from the station. Enough to know that this is exactly the kind of thing that would happen. This is not something I’m ready for. I’m too new. This—all of it—her and I. Anyone and I, really. Out in public. Out. I’m still figuring out how to be. At home. At the banquet, she leans forward in her chair. Claps.

I was present. Sat in one of those ugly chairs long enough. Have an indent on the back of my legs when I stand up after hearing this—the joke (it’s not really a joke, though, right?) and the laughter. I attended. Hoping that nothing awkward would happen. Worrying that it would. “Everyone knows I’m gay,” she’d said on the drive here. “Everyone knows you’re my girlfriend.” I leave the room. Think about what “everyone knowing” means. I don’t look back. She wouldn’t see me if I did. She is watching the pinning. I look around instead. Look to see what “everyone knowing” means. I feel the cold before I open the door and see snow. I count the meanings of “no one cares.”

I am, and remain, present. More than that, I make my presence known. My legs are glued to my chair, but I look across the table. My eyes find the firefighter who shouted, who is now smiling at his own joke and its reception. I say, “Please don’t say things like that.” I want to say more. Maybe explain that the principle of do no harm includes words too. I am choosing my words with care. Don’t say too much, too loud, or too angry. This man is bigger than me and is surrounded by men. Who are also bigger than me. Who consider each other family. And what does it mean that I feel threatened by men who, if a fire were to start at this moment, would lay down their lives for mine without question?

I am present, and included. I am part of the group, one of the guys, so I laugh along—adding to the laughter that swells the room. It’s just a joke. No big deal. The firefighter didn’t mean anything by it. It’s not personal. It’s not about me. These are good people, heroes. People who save lives. Who would rush into a burning building to save anyone. That’s what the night is all about. That’s what we are all here, sitting in these terrible chairs, to recognize and celebrate. It’s an honor to be included.

I am present—in body. My body sinks in the cool metal chair. Retreats inside my girlfriend’s station-sanctioned pullover. Even that can’t keep me warm. My mind, though, is many other places. Questioning if I am too sensitive. Saying words my mouth won’t. It is walking out the door even as my legs can’t. It is back at home, far away and safe—it was never here.

So many chairs.

Later that night, after driving the hour back to my apartment in Colorado, I am the kind of too quiet that my partner has learned to interpret. This is the silence of my thinking deeply, of my mind traversing 5 parallel universes.

When she asks what is wrong, she is lying on her side, turned away from me in bed, facing the wall. I hate it, and hate that I’m not sure what it means. The uncertainty makes my stomach fold in on itself. My floor lamp reveals the hair on my arms standing on end.

“I don’t feel safe,” I finally manage to say, still not ready for past tense.

“What? Where?”

“Tonight at the.” I don’t have full sentences. My mind and mouth seem separated by the multiverse, and she feels so far away. I am going to need many more words to reach her.

Her voice is not sleepy, but tired still. “They’re firefighters. They’d save your life.”

I know it’s true. I’ve already thought this too. The men I met tonight would pull me out of a fire regardless of my sexuality, regardless of my anything. This bravery is profound and incomprehensible to me. My death anxiety is severe enough that I sometimes have trouble falling asleep at night for fear I won’t wake up.

And still, I think, heroism and morality aren’t the same. A person can save my life one day and make me feel unsafe another. Valor does not erase microaggression—they both exist, side by side.

While thinking this, all I manage is, “I don’t feel safe around people I don’t know.” Or maybe around people who don’t know me except that I am someone’s girlfriend. I don’t explain what I mean by safe.

“They are my people.” She rolls onto her stomach so she can look at me now.

I wonder what the alignment means and try not to think of it as choosing sides. I’m trying to work my way back to here and now, to her. I still haven’t explained what happened.

I eventually manage to force out the sum total of two words: “gay joke.” I don’t know why it’s so hard to talk about this. I know that I’m sitting up in bed, but it feels like I’m falling back into that chair instead. I wrap my trembling fingers in a fistful of my sweatpants to keep myself here.

“There are going to be gay jokes.”

At first, I think, “Well, of course.” But then I stop and wonder, “Where?” Not in places I choose to be. I expect I might hear a homophobic slur from a random stranger, and I don’t think it would bother me this much. But this isn’t the same.

I don’t expect to hear hateful language around my friends or colleagues at the university where I teach. And whenever I’ve encountered inappropriate comments in a classroom, I’ve called them out. It’s not okay to talk like that where I exist.

It’s not my reality.

Then, I wonder about hers. She didn’t even hear the joke. Or, if she heard it, she didn’t hear it the way I did. It didn’t register—she doesn’t remember it. She’s been out for a decade. As a former marine and now a firefighter, she is often the only woman in a male-dominated space. Is this something she accepts, ignores, or doesn’t even notice? Am I expected to accept it? Should I? Maybe with time I will stop hearing it, stop caring too, but I don’t think I want to be okay with this.

These thoughts are crowding the path from my head to my mouth.

In my silence, she continues “You’re not going to change someone’s mind about this by—”

I don’t hear the end of this. I no longer feel the heaviness of the quilt around my knees. I have fallen back into the terrible banquet chair. I think about all the ways I occupied it earlier. My absence wouldn’t have changed anyone’s mind, my leaving in protest wouldn’t have, my calling it out might have done something, my laughter wouldn’t have, my silence did not.

The truth is I don’t know that I care about changing anyone’s mind. I don’t enter unsafe spaces to make them safe for others—I’m not a hero. This is something she cares about though. And I do wish I had said something—not to change anyone’s mind, but to point out that words can burn.

I think about the laughter spreading like wildfire around the room.

Even when I wake up back in my bed, some part of me is still—and, I fear, always will be—sitting in that awful chair, afraid, not knowing what to do or who I am.

Morgan Riedl’s work is forthcoming on Entropy, and she was a semifinalist for Ruminate’s VanderMey Nonfiction Prize in 2017. She has an MA in creative nonfiction from Colorado State University, and is now a PhD candidate in creative writing at Ohio University.

Image by Morgan Riedl