“Light as a feather, stiff as a board.” Becca’s friends used to chant this at every sleepover she ever attended in every ranch house on the fringe of every subdivision. Intoning the phrase over and over, four girls at a time assisted in a game that was hardly a game as she now sees it. They closed their eyes for what now seems a holy practice, for what remains as close as she has ever come to leaving her body. Decades later and from her sunless studio in Brooklyn, remembering this game evokes a fleeting attempt at transcendence, of being lifted out of this dimension before all of her friends lost interest and decided to play something different.

Always chosen for levitation because she was the lightest, Becca recalls resisting the urge to squeeze her hands into fists as she closed her eyes and rose higher, almost floated, as each of her friends put two fingertips to her body’s edges. Once they stopped chanting and fell silent, once they left her lying supine on the floor again, none of the girls ever tried testing their powers beyond this. They never tried walking barefoot into fireplaces, never played the Ouija board while trying to summon any spirits. They always watched a movie from the cocoons of their sleeping bags instead. They confessed which boys they wanted to kiss and then practiced, twisting their tongues against the creases of their palms. After they accessed a higher dimension for a couple seconds, they were finished, ready to return to their lives on the ground. As Becca burrowed into her sleeping bag, overlaid with images of ponies leaping over fences, and watched the movie her friends had chosen, secretly she always wanted to return to hovering above the carpet, staying almost weightless.

A late Sunday morning in autumn more than a decade after her last slumber party has ended, and Becca is lying on a mattress without a box spring beneath it. Wearing a cotton shirt fraying at its hem, she stretches her arms and lets her fingertips graze the ceiling. She traces hairline cracks from the bathtub resting overhead in the upstairs unit. Though she lives alone, though she has reached her later twenties without ever having lived with any boyfriends, she still likes sleeping several feet above the rest of her apartment, a space she cherishes for feeling even more private. She has never minded climbing down a ladder to reach her bathroom or kitchen sink. Were someone to invade her apartment while she was sleeping, she believes she would manage in this way to stay hidden here a little longer. Even if she had more money, she doubts she would ever rent a space without a loft bed. She thinks she sleeps better at a higher elevation, even though her unit occupies her building’s bottom story. When she keeps her only window open, she smells her neighbors’ garbage.

Three days have passed since her mom called her from Texas, where Becca hasn’t been to visit since she moved to the city six years ago. With her older brother living only half an hour’s drive from her childhood home, neither of her parents seemed to miss her once she came here after college in Austin, and she rarely speaks with either one. Until her mom’s phone call earlier this week, she always considered her childhood conventional to the point of emptiness. Now lying on her mattress and staring at her phone screen, she is trying to imagine this 16-year-old girl sitting in one of her father’s classes, how the girl must have folded her legs and unfolded them. Squinting into the pixels that form her face, Becca is trying to determine what made her so alluring, what made her worth sacrificing everything that once made her own life feel nearly solid.

Over and over again, she zooms in on the only picture she can find of the girl online. The same image appears on a number of newspapers in West Texas, and Becca is trying to decipher why she became her father’s target, someone he has been sleeping with for a couple years now according to her mom as well as all the media outlets covering this story. In the picture taken only a month ago for the yearbook to be published in the spring, the girl looks less ripe, almost underdeveloped, than Becca would have expected. She appears almost childish for someone whose sexuality flowered with a man in his late fifties. Her face, whose chin is starred with acne, shows no signs of being used to ministering to a grown man’s longings, not at an age when Becca was still going to slumber parties.

Except for a longer nose that looms defiant against the blanker canvas of her cheeks behind, the girl’s features are still struggling for definition. Her dirty blonde hair gleams against a dusky background painted with cloudscapes. Her green eyes, neither round nor almond, look beseeching, stung wide open, and Becca realizes she is probably reading too much into a fleeting expression of someone who in theory should elicit her empathy. Still her face’s shapelessness and thickness of her neck suggest the girl’s inability to control her appetite, her urges. Almost as soon as Becca becomes aware she is blaming the victim, she hates herself for it. Turning toward her wall and then staring into the girl’s face again, she imagines her beaming with satisfaction when she eventually confesses her affair to her friends, who must have felt sickened at the thought of seeing Becca’s father naked. The image of him thrusting with bare buttocks probably explained why one of them told her parents.

A high school art teacher whose sculptures appear in galleries in places as far flung as Santa Fe and Los Angeles, her father has been arrested for what may be only one of several relationships of this kind, as Becca allows herself to recognize as she climbs down her ladder for the first time that morning. She walks to her refrigerator and opens her milk to smell and see if it has spoiled yet. Because it has, she eats only dry toast for breakfast. Once he goes to trial, her mom had said over the phone without elaborating, her father is expected to be sentenced to a decade in prison. In response, Becca wanted to fire a fusillade of questions, including whether her mom ever suspected what was happening, but this was where their conversation ended. Her mom had sounded nonplussed, phlegmatic. Relaying bare facts alone was also characteristic of a woman whose warmth always had clear limits, who always acted as if she was busy even when she wasn’t.

Her mom still works evenings as a waitress at a chain restaurant a couple of miles from their home, off a highway exit. As far as Becca knows, she has never dreamed of doing anything with her afternoons besides weeding the same flowerbeds, besides vacuuming the same carpet while watching the same game shows she has for decades. Whether she has any plans for starting a new life, maybe moving somewhere different, or whether she intends to live alone in the same house as if nothing has happened, Becca has no way of knowing. Maybe hardly knowing each other, though, was always how her family functioned, preserving its own version of normalcy.

Her parents and older brother all assume Becca still works five days a week as a nanny. She may be wasting her life from their perspective, but at least she doesn’t need to ask them for money as, in their eyes, she continues spending her days the same way she has since first moving here. As far as everyone she knows in Texas believes without caring, she still watches the same boy she has since his infancy. While his parents both make unfathomable amounts of money, Becca shepherds their only offspring between play dates, between his Midtown apartment and music lessons involving little more than a room of children beating on drums to their individual and incomprehensible rhythms. After his nap, she takes him to tutoring sessions designed to help children born to privileged parents absorb a foreign language. She helps prepare him for a life that still strikes her as foreign, as exotic.

Though Becca believes she has no claim to her father’s level of talent, she has always thought of herself as an artist. Originally she moved to New York to breathe the city’s more stirring, creative oxygen and see whether her own paintings might find an audience. She has no hopes or aspirations for anything as exalted as having her own gallery. But even while taking out her garbage and riding the subway, her work remains always present in her mind, insistent, even if she feels she executes her visions poorly. However uncertain her lines, however lacking in confidence, there is something in her paintings that exerts a magnetism for those who know how to see them, for those who stand in front of them with a sustained amount of stillness. She feels this herself, sensing a power behind the images unrelated to her skill. She feels grateful for having just enough room in her studio apartment to keep working on her portraits of beings yet to come into existence.

The paintings are all of animals with human faces. The birds have human eyes, sometimes human lips, lending the animals an oddly human expression. Becca paints all her hybrids—lions with childlike and stubby noses, silverback gorillas with human eyebrow arches, ostriches with beards resembling all the bartenders in Brooklyn—in the space beneath her loft bed, between her ladder and the few square feet serving as her kitchen. Her easel stands just outside her closet, whose top shelf is stacked with paints and canvases. Whenever she finishes a painting, she takes it to a storage unit a couple blocks away. Though occasionally she tries selling her work online or at street fairs on weekends, most people don’t enjoy recognizing themselves in another species. They don’t want to admit this might be humanity’s only way of accessing a sustainable existence—the loss of individuality for collective balance.

Becca is only able to spend as much time as she does painting the only version of humanity she can envision surviving for much longer on this planet because a couple years ago she started answering ads to serve as a nude model for other artists. Some wanted her to pose for them in private, though most paid her to model for their classes. After only a month of this, Becca was filling most her weekday evenings by undressing and then holding poses that gradually drained all the blood from her limbs, left her muscles aching. As the weeks kept passing, she also found she was able to do this more easily, staying stationary for as long as twenty minutes at a time as she inhabited a stillness that quieted her thoughts to almost nothing.

Sometimes as she sat staring out onto a room of people trying to render all her contours and proportions, some of the faces seemed to transform into rabbits, while others became tortoises or horses. Birds, though, predominated, perhaps because Becca has always sensed these are the creatures among whom she herself belongs, among vertebrates spending most of their time avoiding the ground, preferring the firmament. Given the option, Becca would have chosen wings and the ability to fly vast distances. Her eyes have always been large to startling, especially against her smaller lineaments. Sometimes to onlookers, to those who paint and draw her body, she strikes them as too delicate, causing them to worry.

After several months of modeling for the classes he teaches, one of the artists who hired her originally asked if she would be interested in something more complicated. Before mentioning what he had in mind, he said he would be willing to pay her considerably more money. From the glint in his charcoal eyes, from a warmth in his voice rising from his abdomen, Becca knew no matter what it was she would do it. By then, Yuri’s presence had acquired for her the texture of a blanket, and she felt herself yield to his reservoir of calmness before she knew this would be necessary to do what he now wanted. Within only a week of working for him in this new medium, she found she could shorten her work week to only three days as a nanny.

In its purest form, the practice invites entry to a space that feels almost sacred, a realm of relinquishing. Everything hinges on surrender. Otherwise, there would be pain, certainly panic. This way of earning money is also, as Becca realizes, as close as a woman living in New York City can come to levitation, to reliving what before was only a game at slumber parties. After Yuri binds her in rope whose knots reveal his fingers’ deftness, he hangs her from his ceiling. First he photographs and later paints her as she flies with her wings clipped above him, with her scapulae almost touching. In the course of only two sessions, each lasting three hours, he pays her enough to meet almost her whole month’s rent. Though Becca is always naked as he wraps her in rope he threads smoothly as ribbon, though the patterns he creates between the knots against her skin serve an erotic purpose, the photographs he takes of her serve only as templates for his paintings. Her face remains hidden in them all. Becca believes he is careful about this. He assures her he doesn’t want to risk exposing too much of her despite and because of all she is willing to give.

The jute ropes he uses encourage her to close her mouth and eyelids, to say nothing as he works. He has told her the word “kinbaku” in Japanese means “the beauty of tight binding,” and she senses a tenderness accompanying Yuri’s movements as he pulls the rope around her waist or thighs or buttocks, as her constriction becomes almost a form of protection against outside forces. Yuri studied kinbaku along with other martial arts practices in Japan for several years, he told her when they first started these sessions. Though she believes she could sleep with him if she wanted, he has never made advances. Though he keeps silent as he works, he told Becca once afterward while she was dressing how her aura of innocence helps to heighten the effect of his binding. About her, he almost whispered, something otherworldly emanates. Becca is unsure whether this is a good thing.

Since her mom called about her father, part of Becca wonders whether she would be doing this if he had not committed the crimes he has for who knows how long in reality. Asking herself if she has suppressed some knowledge, she realizes she has repressed not so much facts as a feeling, a sense of her father being subtly invasive. The girl with the long nose out of place among her face’s other expanses has resurrected memories of habits from her childhood that have never gone away, not entirely. She remembers sitting in her kitchen as an adolescent and wrapping rubber bands around her wrist until her hands turned blue then purplish. She remembers her mom turning from where she stood washing the dishes and rolling her eyes at the change of color in her daughter’s skin, believing Becca to be indulging the typical useless lethargy of adolescence. Alone in her room, she also used to tear off the ends of her fingernails until her fingertips turned bloody. As her body threatened to turn into a woman’s, she began restricting her diet to keep herself from assuming her mother’s same obtrusive proportions.

Though she has never felt as close to either of her parents as her brother, she cannot help wondering whether her almost daily urge to escape her body, to float above her life rather than inhabit it, finally has an explanation. She wonders whether part of her knew what happened, even when she slept at friends’ houses on weekends, whether part of her suspected what her father may have been doing all along inside his art studio on her small town’s outskirts, inside a studio amounting to little more than a shed far from the town’s central businesses and traffic. Maybe there was always a reason for her never feeling grounded, for never wanting to be. Or maybe her dad’s sexual predation, her mom’s stoic responses, have nothing to do with her lifelong sense of not belonging—not to this world, even this species—but only reflect her own underlying strangeness. All she knows for certain is the closest she now comes to feeling at home in her body is when Yuri places his hands on her, when he ties the knot a little tighter, restricting her freedom of movement.

Becca and her father haven’t been in a room alone together for what now seems like ages. Whenever they were, she never thought any harm would come from their physical closeness, from conversations that only reinforced her feeling nothing ever happened here, not in a place the rest of the world never knew about or had forgotten. There were still times when she caught him looking at her body with what she felt was too much interest, more than she wanted. Once she started wearing a training bra, she remembers how he used to rub her back over and over again, taking too much time to acknowledge her presence. He began making this a habit whenever he found her sitting at the kitchen table doing homework or as she lay on her stomach watching TV. She knew he wanted to feel the lines of the elastic against her skin, and he wanted to do this repeatedly. It is only now she has remembered how he gave himself permission to indulge at least this much curiosity about her body. Sometimes as she sat eating her dinner across the table from him, as she approached him in his studio when he was carving blocks of wood into figures of voluptuous women, he would stare at her breasts directly, something even Yuri avoids when she is naked. Becca is still unsure if all fathers look with the same wonder as hers did, if they all gape at times without apologizing, displaying a desire of which they seem unembarrassed.

The town where her parents live is flat and barren, pockmarked by sinkholes constantly threatening the collapse of roads and bridges. The oil and gas drilling dominating this part of Texas has, over time, punctured too many holes in the earth for the ground not to founder in places. As a little girl, she used to wake breathless from dreams of falling, sometimes through the air with no ground beneath it, sometimes with more of a sinking feeling, which took its time leaving even once she sat up conscious in her bed. She used to change her clothes with her window shade closed tightly to the ledge, all while wishing her door had a lock so no one could walk inside by accident. The sheer amount of emptiness by which she was surrounded—the immense stretches of parched prairie, the low clouds grazing desolate mountain ranges, the abandoned strip malls and rows upon rows of foreclosed ranch houses—also made her long for crowds as a form of protection. Ever since moving to Brooklyn, Becca has enjoyed walking through vast swarms of indifference. She has nowhere to fall here except onto the floor of her apartment, which feels more solid to her than in Texas.

When she knocks on Yuri’s door later that evening, he is standing at his easel. He is listening to music both of them find soothing as he paints from a Polaroid of Becca he has clipped to his canvas. In place of the ropes that normally bind her in this series of paintings are stretched the tentacles of an octopus, an imaginative license she has never seen him take before. As they have gotten to know each other better, Becca has shown him more of her own artwork, though only as photos on her phone, never in person. In response, Yuri has only ever nodded, never offered an opinion. He has only smiled, as he would toward a child who had shown him drawings of her family, stick figures standing before an A-frame building. Now studying the reach of the octopus across her body, Becca wonders whether he has drawn inspiration from her own hybrids, which she once considered works of prophecy. She wonders whether Yuri also sees the benefit of mixing species to create something more lasting on this planet.

Hearing her approach, Yuri turns toward her and smiles with a recognition that seems to hold a lifetime of knowing. To Becca, this glance is sustenance. Though she would never come here if he studied her with sexual interest, part of her needs—survives on—his attention. There are so few people who know her in this city, and Yuri’s quiet gazes have become their own nourishment. Though he is more intimately acquainted with her body in some ways than she is, a comfortable space abides between them. He looks but without any avarice, with something closer to curiosity, something that allows him to imagine her mating with other animals to create an entirely new life form. As he wraps the jute around her back, her waist, her shoulder blades, Becca feels safe from the world again, from all that happens down in Texas. Knowing her father is now going to prison, she feels grateful for the fact Yuri is lifting her so she can hang from a truss attached to his ceiling. With no way of escaping this place until he finishes his sketches and takes all the photographs he feels he needs, Becca feels protected. Within the next few hours, he lowers the chain from which she dangles helpless. With his normal gentleness, he unties all the knots he has made. Though his hands are cool, their touch is one of softness.

After Becca returns to her apartment, she checks the websites of all those newspapers in Texas following her father’s story. In the article covering his case with the most depth, alongside his mug shot are photos of his studio as well. His sculptures, all of human bodies, most of women, can be construed as evidence. Closeups of his work appear to hint he’d been leering at young girls as he fashioned his figures’ hips and buttocks. The jaundiced light cast by his burlap lampshades renders everything dirty and putrid despite the fact he kept his space even cleaner than it needed to be. Years ago, he started tacking his old license plates along the ceiling beams, and even this now seems suggestive of someone who intended harm all along, a man who never drove with an outdated plate to avoid being tracked by authorities. Even though he was an artist, he still drove a pickup truck like everyone else in this part of Texas, maybe trying to better blend in with the anodyne masses.

Examining the photographs more closely, Becca sees something familiar afresh, something even the author of this article has missed in his analysis. Her father has scattered his studio with bright blue objects. At first glance, they seem to only offset the blankness of the white walls. But all his trinkets—random ceramics, paperweights, even old soda cans—are colored a dazzling blue that Becca remembers attracting her eye when she was younger. Only now does she recall loving to hold so many shards of blue things—smatterings of topaz lining the window ledge, cornflowers overflowing a glass vase, even the blue leather case for holding his glasses. He once told her when she was a teenager, after she had come closer when he asked her to sit beside him, how male bowerbirds in Australia and New Guinea build bowers out of sticks, bowers that serve no purpose except to display the birds’ own prowess and beauty.

Becca remembers laughing as he said this, but his eyebrows had knitted themselves closer together as he added the male birds’ feathers were tinted indigo, and the brighter blue objects they gathered helped to draw the females’ notice. The bowers these birds built were the genesis of all art then. The careful arrangement of their sticks and myriad blue objects they culled as decoration formed the raw material of a creative process millions of years older than the oldest cave paintings. Becca’s father had squeezed her shoulder where her bra strap should have been but had fallen down her arm instead as he cleared his throat and said that, since they both were artists, they both deserved a bower, a place of privacy where they could display their beauty. At the time, she thought he meant his sculptures and wood carvings, but now she knows he meant a place to display his full wingspan, a place to reveal the part of him that came alive only through making love to vulnerable young women.

The next time she sees Yuri, he notices a difference, something fallen that previously had stayed aloft inside her. He asks what is wrong, and knowing his concern is genuine, Becca lies and says she is tired of working as a nanny. Trying to sound convincing, she says she sees no future for herself here anymore, something she realizes must be true as she hears herself saying it. She sighs and reflects in all seriousness that her life here lacks purpose, sustainability. Her lie has yielded some truth, and she admits to herself for the first time that she can hardly keep making a living being tied from his ceiling, becoming a drying piece of fruit hanging pendant from Yuri’s branches.

She has no other profession in mind. She isn’t working toward anything of any more promise. She looks away from Yuri toward the coil of ropes lying in the corner and does not mention anything about her father. Still he senses this is not the time to tie her into something smaller, more contracted. As Becca begins undressing, he tells her to wait. Glancing toward his easel, he asks her to stand behind it. He says he’ll pay her to paint him for a change, for a session, and Becca feels a little ashamed of having elicited his compassion. She starts making excuses, saying she cannot draw from life—she knows because she tried in art college—but Yuri is already shirtless. Becca laughs at how swiftly he leaps into nakedness, and he teases her about not being mature enough to handle male nudity. He tells her she can do anything with him she pleases—make him into a fish or dragon or elephant—but she must stay silent, no more giggling. She has three hours to paint him either as he is or transform him into something that has never existed.

She doesn’t know what to do with this new freedom, but her hand glides with ease across the canvas. In her hands, Yuri begins dancing in the air even as he relaxes on the floor in front of her, muscular and languid. In her painting, he is also winged. He is a bird who has not built her a bower but has given her the gift of seeing herself clearly. His brown eyes have never looked at her, as she believes, with sexual interest, and this may be why she loves him. Regarding his display of flesh unbounded, she knows this. The knowing too is enough for the present. Whatever happens, she is not in a hurry.

She paints him flying toward the top of the canvas, above which she imagines she herself is floating. He may either float and join her at a higher elevation or help bring her lower, closer to the earth and all of New York City. Once she finishes her painting, whatever had fallen inside her has risen again. They do not make love this evening, but some loving still happens. After their next session, Becca invites him into her apartment. She shows him all the other birds with human eyes and expressions—shows Yuri he is in this sense only one of many—and knows she is making progress. After he leaves without seeing where she sleeps, without climbing the ladder to her loft bed, she allows herself to surrender to something more than being bound with rope, surrender to longing.

When Becca’s father calls her a week later from Texas, he tells her what she knows already. He is going to prison for at least a decade, and he says he is sorry, though she does not believe him. After a period of silence, he says he loves her, and she does believe him about this, however. She does not know how to forgive him or if she will ever see him again, but she knows the fact he never did more to her than feel her bra strap may have been his one enduring act of selflessness. By this time, three other former students have come forward and confessed they either slept with or were fondled by him, all against their wishes. It is now nine on a November evening, and she still hasn’t eaten, though she normally never does after a session with Yuri. His eyes and his hands always leave her too full of nourishment, of solace. Her father says again that he loves her, and this is where she leaves things, with him loving her as best he can but loving her badly.

Melissa Wiley won the 2019 Autumn House Press Full-Length Nonfiction Contest for her book “Skull Cathedral,” concerning the body’s vestigial organs. She is also author of the personal essay collection “Antlers in Space and Other Common Phenomena” (Split/Lip Press, 2017), and her work has further appeared in places like American Literary Review, Terrain.org, The Rumpus, Entropy, DIAGRAM, Phoebe, Waxwing, The Offing, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, and PANK.

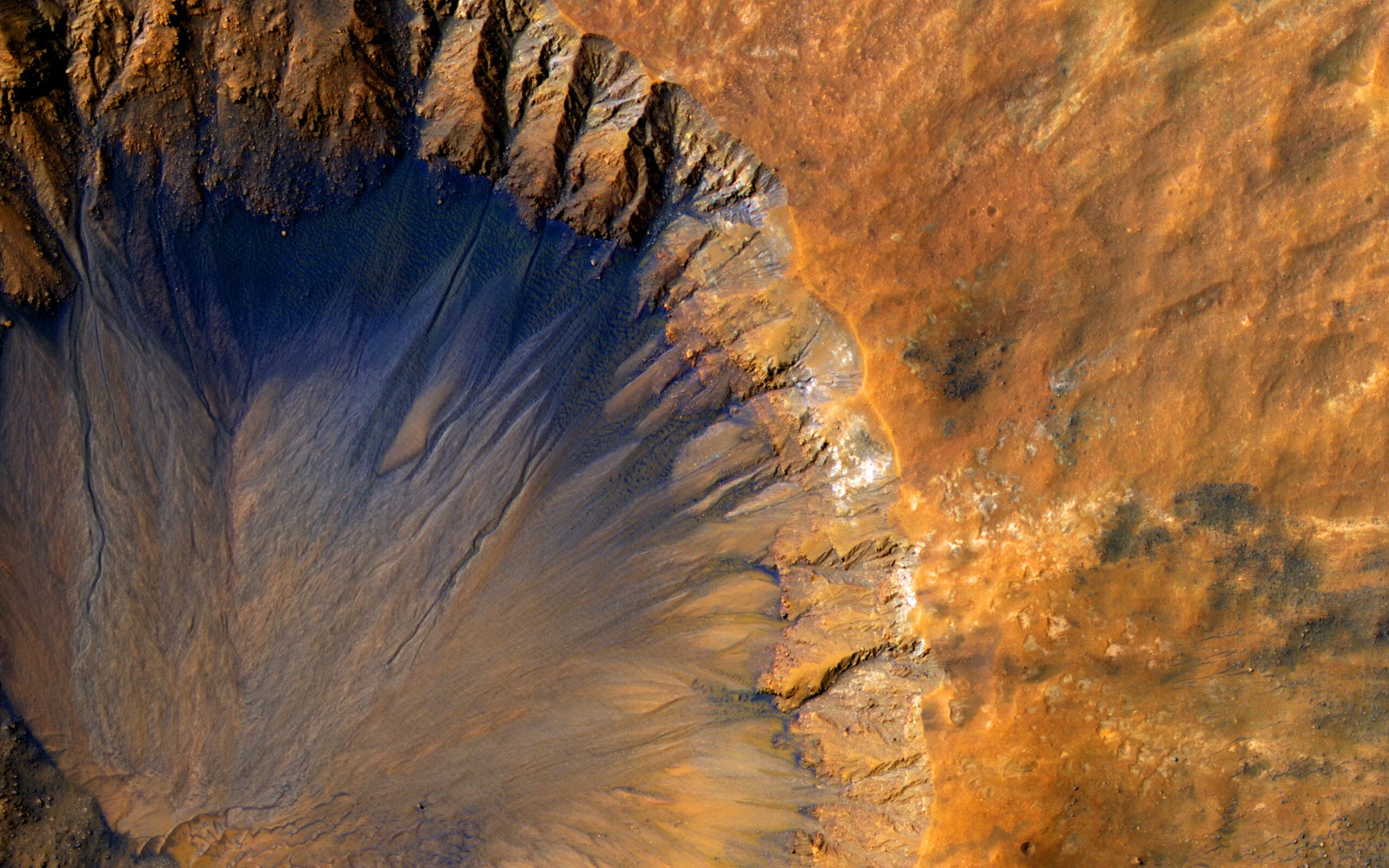

Image by NASA