According to Jan Krufka of Hard Facts Magazine, my studio apartment was a musty, dank lair. He told his readers about the tissues I had tucked into the crevices of my corduroy couch. The once sky-blue walls were moss green. Most of the light bulbs had fizzled out. Jan said he could tell I spent all of my time on the couch, since the fabric had worn away in the shape of my body, mimicking a chalk outline at a crime scene. He wrote that I must have acclimated to the stale stench of sweat soaked into the cushions, but that he could not resist flaring his nostrils in disgust when he sat beside me.

I threw the magazine on the floor and slid a thermometer under my tongue. My fever held strong. It burned my insides and warped my vision. My skin was hot, but I shivered. I opened and closed my hands and imagined creaking noises when I bent my fingers. It was only April, and I had my third fever that year. A personal record. That one hurt more than the others. I always get grouchy when I pass 101, and I had just hit 101.2. I slapped some ice packs on my inner thighs and knocked back four Advil.

By mid-April of the prior year, I had run only one fever. My self-flagellation had been about volume, the sheer number of diseases I could catch, but last year’s fever set my record for highest temp. 105 flat. A fever that high turned me into an infant. I curled up, knees to chest, imagined I had a partner to pet my head and tell me I would be okay. My memories of the hospital visit are vague. A doctor kept his stethoscope in his ears while he told me to cut the gimmick. Another doctor massaged my shoulders while seated in front of me, staring into my eyes, telling me I had pneumonia.

This year alone I have contracted a run-of-the-mill flu, scurvy, and pneumonia, which for years was a slippery little bug. The beauty of pneumonia is that the body becomes more receptive to it once it has been infected. I spent the better part of five years trying to catch pneumonia, but once I caught it, it remained a constant in my life. If I ever have a healthy spell, I linger in an ER waiting area, and I’m practically guaranteed to get it. Helpful as it’s been, I know I can’t count on pneumonia forever. Those chest-caving coughs, those limitless fevers, those concussive migraines. Past fifty, pneumonia could kill me. Past fifty, lots of these diseases could kill me. I try to push those thoughts to the back of my mind.

People always ask why, but that’s the one question I refuse to answer. And at this point, I’m not sure I remember why I started. I’m like a birdwatcher, seeking out free-floating species, crossing essential names off a list. I’ve travelled overseas to contract certain illnesses. I’ve drunk toxic chemicals, let snakes and spiders bite me, dunked open wounds into stagnant ponds. I can’t imagine getting any more reckless. I’d have to start swimming in bull shark nurseries.

In my younger years, I oscillated between a total recognition of my own mortality and a youthful negligence toward my future. I experimented with eating disorders, and I ran marathons during week-long fasts. I stood with a sloped back and wore shoes with no arch support. I drank forty ounces of coffee on an empty stomach. I slept for an hour a night during the week, and I slept for thirty hours every weekend. I smoked cigarettes while packing a lip of mint grizzly. Fell asleep while I chewed nicotine gum.

But the system began to fail. My slender cheeks became sallow and jaundiced. Chest pain and tunnel vision plagued me. A throbbing pain in my thoracic stalked me. My knees resisted full extension. The weekend hibernations slowed to sporadic naps. I fixated on the sensations which I thought were symptoms of impending death. Any more than a cup of coffee and I’d have a world-ending panic attack. I quit tobacco and caffeine cold turkey. For months I felt a relentless tugging at the backs of my eyes. My cranial gyroscope rotated perpetually, never figuring out which way was up. The blood vessels around my eyes burst from my lachrymose nights. My sister said I looked like a beaten child. I said that would be a few rungs up from where I was.

After losing the bodily fortitude necessary for meaningful drug use, I wandered aimlessly during the day. Running was no longer an option for me since any sudden elevation of my heart rate incited panic. So I walked. All day I walked. I would count my steps. Count cigarette butts. Stare at people, see if I could read their minds. I would worry that they could read my mind. I feared death but contemplated suicide.

But at some point, I had to figure out how to live with a body. I had no companion to whom I could vent my problems, except for a puppy, but he had no advice for me, only sleepy eyes and moist accidents.

I began seeing a therapist, Dr. Pletcher, who wore a Grateful Dead T-shirt and a bandana like Rosie the Riveter. His waiting room had an empty fish tank and a Persian rug, which I assumed was stolen. The receptionist wore headphones while I spoke to her. She made copies of my insurance card. When they finished printing, she dropped the copies in the shredder. The office smelled like cat piss and broccoli. The white paint had yellowed and cracked, and moisture striated the ceiling tiles. The couch I lay on to confess my sins probably carried a disease that started with an H. Pletcher used his index fingers to put single quotes around words like ‘doctor’ and ‘anxiety.’

When I said I had trouble completing the simplest tasks, he said, “It’s all in your head, man. You shouldn’t be so self-conscious about your height or your weak chin.”

I said, “I’m not.” I knew he couldn’t help me, but I paid the copay to listen to his slapdash solutions to my problems.

He suggested a series of exercises to find out which of my family members were trustworthy, and from there I could build a support system. He told me to call my mother and hang up each time she answered and count how many times she picked up the phone. I was to repeat this exercise on my sister and brother. According to Dr. Pletcher, I should break contact with the family member who answered the fewest calls. When I tried what he dubbed “The Cloying Call Experiment,” each family member answered twice. He told me I must have been doing it wrong.

Pletcher said therapy alone would never solve my problems. He insisted that I take pills from an unmarked bottle. When I said I didn’t trust his pills, he said, “Who’s the doctor here?” To prove the pills were safe, he took two at the beginning of a session. Within minutes, his shirt had darkened with sweat. For the remainder of our fifty minutes I sat quietly while he listed state capitals in alphabetical order. That night I dumped the pills down the toilet. In our next session I told him they were helping. He told me that if anyone asks, I didn’t get them from him.

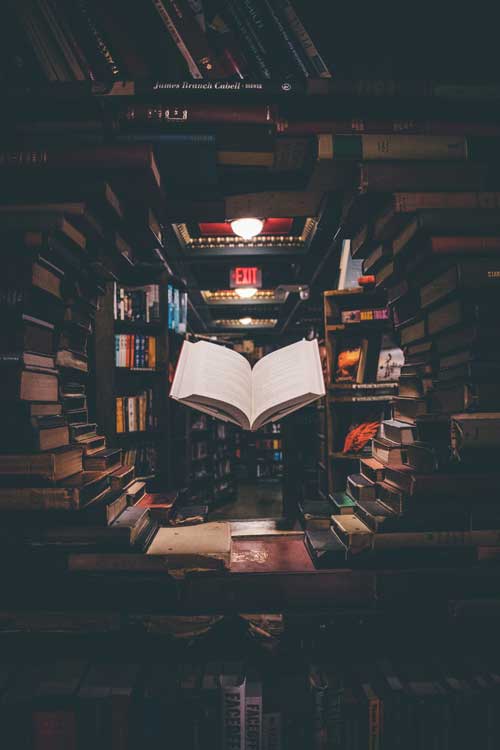

Per Pletcher’s advice, I went to The Last Bookstore on the Left in search of a biography. Somewhere in that bookstore, there had to be a book of answers. Perhaps a biography could provide a worthwhile template. Someone must have lived a life that I could transplant onto my own, a sketch of life that I could trace and use as my daily crutch.

Standing inside the store, feet away from the revolving doors, was an empty piñata, made in Julius Caesar’s likeness. Any customer could enter to win the grand prize of smashing a Roman dictator. In each corner of the store, men in overalls spread off-white paint over the mock recreation of Michelangelo’s ‘The Creation of Adam.’ In a Californian twist, the store’s ceiling had Adam high-fiving God, who wore a backwards hat and a pair of sunglasses. A scrawny, long-legged teenager with a Britney Spears style headset microphone organized a shelf of self-help books. I asked him if he knew of any good biographies about someone with values. He handed me a new diary, still wrapped in plastic. With an index finger he tapped his temple, looked me square in the eyes, and nodded his head.

I found an old man standing atop a ladder, stacking overstocked books above a shelf. I asked if he could help me, and he descended the ladder glacially. When he dismounted, he came within inches of my face. He was too old to perform manual labor, and he mumbled phrases like “just another day in paradise.” I asked him if he could recommend any good biographies, and he said Jean Harlow was a real firecracker. I asked him where I could find her book, and he said he didn’t work there.

A young man overheard my discussion with the elderly patron and guided me by my elbow to the auto/biography nook. He told me fat chance finding a book on Jean Harlow. He recommended Theodore Roosevelt’s autobiography. He said it would teach me what a man is, how a man should behave. I told him I wasn’t interested in that sort of thing. I said I’d rather model my life after the elephant man. He asked if I meant the movie or the book, and I said the person.

I spent hours reading the final chapters of every presidential biography I could find. If each final line pithily summed up why I just read the preceding few hundred pages, then none of these biographies were worth their ink. I settled on Tim Allen’s autobiography, Don’t Stand Too Close to a Naked Man. A press quote on the cover called it, “A scathing indictment of American culture…Satire as devastating as a drill bit.”

There were two registers at the front of the store. On the left, ten customers stood dead-eyed and hopeless. On the right, the elderly man argued with the cashier, who insisted the store didn’t sell Hellman’s mayonnaise. I figured their discussion couldn’t last more than another minute. I got in line behind the old man, and he pointed to me and said, “My cousin told me I could get some mayonnaise here.”

The cashier looked at me and said, “Well your cousin’s an idiot.”

“Keep me out of this,” I said. I thumbed through Naked Man while the chaos continued. The elderly man referred to me as his cousin again, then as his caretaker.

While I thought about how I would do my best to give him some comfort during his last few years on earth, I congratulated my imaginary self for being a good person. His voice cut through my daydream. “Hey smiley,” he said. “Let me see that book.” I handed it to him, and he paid for it. All he asked in recompense was company during his walk home. I would have refused if he hadn’t already paid for the book.

During our walk he called me Badger, and he told me jeans had become too expensive. His name was Marvis and his wife’s name was Mavis. When he asked why I needed a biography, I told him about my assignment.

“What a load of guano,” he said. “No one can help you find wisdom. Just listen to Emerson, ‘trust the self.’”

In a serpentine sentence I dare not try to recall verbatim, he told me not to search for the meaning of life in a bottle. He said he revolved his youth and middle-aged years around vodka, and he now has something called wet brain.

“I poisoned myself every day for twenty years,” he said. “It was no way to live. I might as well have been standing around in Porta Johns.” He said because of his illness he missed out on life, just like when he was a kid and had the stomach flu. I disagreed with him. He drank to escape life. He drank to live in absence, to forget. But when people have the flu or pain in general, they are more aware of life than ever.

When we got to his apartment, he invited me up for coffee. I told him I had had enough excitement for one day. He turned and left without speaking—my favorite type of goodbye.

I decided to walk home, which was about four miles away. I had nowhere to be. Within twenty minutes my arms and cheeks were pink with sunburns. I drew suspicious glances in good and bad neighborhoods. I thought Sunset Blvd. was the best route home until a car hopped the curb and killed a pedestrian about a quarter mile ahead of me. I took the neighborhoods.

Hours later, I reached my street. With soaked shirt and pants, I sat on the curb and let the dry breeze cool me off. I closed my eyes and imagined the wind bending to the contours of my body, enveloping me, swaddling me like a newborn. The walk across town caused my body to feel like it was still moving forward. I swayed my torso, hoping this would correct my motion sickness, but my discombobulation turned to nausea. My eyes no longer felt accustomed to the sun. My pupils must have shrunk to microscopic apertures. I positioned my hands above my eyes into a make-shift visor, and I dry heaved over the gutter. When neon bile creeped out of my mouth, a voice asked, “Are you okay? Do you need anything?”

Without looking up I said, “So thirsty.”

“We have water inside. If you want to come in, I can get some.” I looked up and saw a face I had seen and ignored nearly every day. It was a mother who lived across the street from me. She had two kids who toilet papered their own house a few times a month.

“That would be great,” I said, forcing an appreciative smile. I struggled to stand and had to pause to recalibrate my balance. I followed her toward the house, trying to think of a pleasant conversation to interrupt the silence. “Thanks for letting a sick stranger into your house.”

“That’s all right,” she said. “We already have a house full of sick children. What difference is one more?”

We entered the house through her garage, which led directly into her TV room. Inside, eight children lay on couches and inflatable mattresses. Each child had a pale complexion and moist hair. Some had spots on their cheeks and foreheads. The children wore oven mitts on their hands with excessive amounts of tape fastening the mitts to their wrists. While the mother fetched water, I stood staring at the children. None of them looked away from the Bruce Willis film playing on the TV. Occasionally a child would attempt to scratch themselves, but the mitts occluded any attempt to relieve the itch. The mother returned from the kitchen with a glass of water and a multivitamin. “Here,” she said. “These should help.”

“Thank you,” I said. “What’s with the gloves? Are you giving the kids a lesson in kitchen safety?”

“No,” she said. “My Jacob and Arnie got chicken pox. When word got around, everyone sent their kids over so they could catch it too.”

“Why?”

“To get it out of the way. Bite the bullet. The kids will get it anyway. Might as well get it when their friends get it. When it’s as good a time as any.”

“Don’t they have a vaccine for that?”

“I can’t speak to the other parents, but the boys were born in a country that wasn’t quite as friendly toward vaccinations.”

I stared at her in silence, admiring the wisdom that comes with parenthood. It takes a level head to expose one’s kids to an illness intentionally. It reminded me of the one time I watched my nephew. It was my first experience taking care of a toddler. My sister had to negotiate the price of the cotton candy machine for her kid’s party—typical of my family. For two hours I tried to keep my nephew away from the markers, as I knew he would draw on himself and get me in trouble with my sister, whose affinity for me had plummeted in recent years. When she got home and he started to irritate her, she handed him a marker and told him to go draw on his legs. I told her he’d be covered in marker, and she said, “What do I give a shit?”

Two kids collaborated through mitted hands to change the channel to a cartoon. On the show, a cat with human hands pried off its nails with a flathead screwdriver. One of the children boasted that he could remove his nails if he had to. Another kid said so what. The youngest looking boy unwound the tape from his glove’s wrist. He squeezed the glove under his right armpit and freed his hand. By the time the mother noticed, the kid had blood trickling down his cheek and a grin of relief.

I threw the multivitamin into my mouth and sipped the tap water. The pill spent too much time on my tongue. It tasted like a horse stable. Because it was nearly the size of a tube of Chapstick and my throat was an arid wasteland, the pill slithered down my gullet slowly, stopping to view the scenery on its way to my stomach. Trusting in this mother’s presence, I was able to think objectively about my body for the first time in months. In this room of exposure, the children exposed to disease and myself to a textbook example of a choking hazard, a preternatural surge coursed out of my gut, through my limbs, into my brain. For the first time in my life I was forming an idea. From there I would turn it into a goal, and after that I would make it a lifestyle.

I guzzled the remaining rust-flavored water and handed the glass to the mother. “Thank you for your help,” I said.

“Feeling better?” she asked.

“For the first time,” I said, “I feel terrific.” On my way out I heard the mother scold a child for saying “butthole.” I crossed the street, practically dancing, glancing down at my bile, which the sun had baked into the asphalt and transformed from a neon hue to a swampy green. When I reached the front door of my building, I took a quick look around, hoped no one was watching, and dragged my tongue across the door handle. It tasted eerily similar to my neighbor’s water, the only difference being the door’s salty aftertaste.

Like a junky taking that first hit of H, experiencing that orgasmic, maiden nod, my life reached a new epoch, one that would exist only to quench a hitherto inconceivable urge. In college, my first roommate, Chris, had OCD. His most inhibiting behavior was his doorknob aversion. Chris would stand outside our apartment building, either waiting for someone to come in or out or for me to come down and let him in. He said he sensed a presence on his hand if he touched a doorknob, as if it burned his skin. His doorknob aversion ruined relationships, spoiled job opportunities, and damaged his kidneys and bladder irreparably, for the unfortunate man found nothing more repulsive than a restroom doorknob. I bought a pair of gloves for him and his mother forced him to change roommates, calling me the worst enabler she had ever met. I’d commit fratricide to force Chris to watch me touch my mouth to a doorknob. His head would explode.

Following the diametrically opposite path to my old roommate’s, I grew intolerably anxious when a doorknob went untasted, not to mention untouched. If circumstances would not permit discreet doorknob licking, no one would stop me from holding the door open for strangers, secretly soaking the door’s essence into my palm. Then, when the time was right, I would lick every square inch of my hand. No need to waste the schmutz that gathered in busy entryways.

I spent my time touring the city. The library had some terrifically filthy door handles. Their taste lasted the longest, except for the bathroom doors in the subway stations—the taste of which blew my hair back. I refused to wash my hands, for I knew with sustained negligence they could accumulate the filth of a public bench. I had a recurring dream in which mushrooms grew between my fingers, and I cut them off, cooked them, and ate them. Their taste was mediocre. However, the mushrooms would spread to anything I touched. Soon enough, like Midas turning everything to gold, my home became a mushroom sanctuary, a mycophile’s paradise. The dream ended with my dream self reaching deep into my mouth, thereby causing mushrooms to grow in my throat and obstruct my breathing. Before I suffocated, I awoke hyperventilating, leaking spit into my bed.

The corollary for this way of life was illness. I contracted any seasonal bug, any cold that was going around, any disease verging on epidemic status. I became a walking sack of phlegm. Tissues filled my pockets and wrists of my sleeves. I had to stop wearing black shirts. When one spends enough time with a leaking nose, one learns the first law of phlegmy fashion: the darker the shirt, the more visible the snot. The ill person must eschew gray clothing, since any moisture accumulated in the underarms and on the back peeks through the shirt. And once the gray-shirted person notices the first signs of sweat, the floodgates open and there is no telling how wet the shirt will get.

As my sicknesses accumulated and my clothing spoiled, I began to take notes on the symptoms, sensations, and terrors of each illness. The symptoms were simple enough. I would log the physical manifestations of each malady—fever, cold sweats, headaches, and so on. The sensations were more abstract and required keener attention. I had to ask myself which body parts felt more sensitive than usual, which senses were dulled or heightened, which discomforts rose and fell. Terrors, while the most abstract factor, required the least attention. Terrors were the facets of an illness that caused mortal concern for the inflicted, independent of whether mortality was at risk. The terrors were chest pains, bouts of severe dizziness, blood in stool and/or vomit, and any other symptoms that trigger thoughts of death.

Tragically, like all delicacies, the taste of doorknobs lost its appeal. The compulsion never left, but the pleasure did. It was my first real brush with depression since I began my new way of life. I made a supplication to all gods, in case any were real, asking them to reignite my enjoyment. Because of my feeble nervous system, drugs and alcohol were not an option. I gave up cutting in my teenage years after a fellow cutter went a little too deep on himself. I might’ve been depressed, but I wasn’t ready to wipe my slate clean. The only constant source of change was the unending list of symptoms I had to endure from catching every common illness possible.

All my prior pleasures had left me. No joy in eating or smelling daisies, no ecstasy in orgasms or sneezing. But no one ever adjusts to a fever. No one adapts to chills and migraines and body aches. With the exception of a few weeks out of the year, I was operating under a constant fever. Everyone needs a fix. I had to accept that illness was mine.

I would lay in bed and fill legal pads with measurements and musings on these diseases, and for my own reference, I kept detailed files on my bodily reactions to each one. When my sister realized what I was doing, she told me I was practically guaranteed to get a fanbase if I published my notes. I told her no one wants to hear about shit and snot, and she said that’s all anyone wants to hear about, especially when it’s coming from a weirdo. She said she made more money that year from her blog than she did from working as a paralegal.

Per my sister’s advice, I digitized my notes and started a blog. I made the blog as user-friendly and comprehensible as I could. I eliminated all Latin, medical jargon, or byzantine language that upholds the patient-doctor dynamic. The website used street names for maladies and cures. I called it The Germ Chaser. Much like the storm chasers who catalogue the conditions of tornadoes and hurricanes, I was following the microscopic germs that challenge the body’s structural integrity. By exposing myself to viruses and bacteria, I was gathering data that physicians could understand only secondhand.

Perhaps this is why the blog grew as rapidly as it did. Mine were the facts of the people, the proletarian measurements. I answered the most important questions: how will I feel, for how long will I feel that way, is it dangerous, and what should I or should I not fear? I also included the information that WebMD and other such sites refuse to include, since that damned site wants the reader’s hypochondriac tendencies to spike. For each illness I included a page titled, “How you know you do or do not have it.” No fever? That means no MRSA. You can still complete your five-mile run? Perhaps your anxiety and posture are provoking your chest pain. No coughing? It isn’t pneumonia. The blood in your stool is bright red? The bleeding isn’t internal.

When the blog exceeded 100,000 visitors and the interviews started, I stopped concerning myself with popularity. Germ chasing was never about popularity anyway. It was never even about the public service I was providing.

The challenge of getting sick as often as possible is that a stable job cannot last. Advertising on the blog became my only source of income, and it was more than ample. In retrospect, I wish I took the process of selecting advertisers more seriously, instead of choosing each one ironically. The blog advertised three different types of boner pills, Cricket Wireless, and Scotch tape. With the exception of the boner pills, I doubt these ads helped my readers. But I could quit my day job and dedicate myself to illness.

At first the interviews were a drag, but they felt like a necessary way to build a following. I figured out that I could exploit journalists within reason. In exchange for an interview, I required the interviewer to bring cough medicine and mentholated balm. I realized if I could stop buying those two essentials, I could start saving decent money. Fortunately, newspapers and magazines found these expenses inconsequential, and they asked in exchange that I keep the hostility to a minimum. I met my end of the bargain half of the time, leaning on the excuse of “sorry, I don’t feel well,” when I went too far.

With the Krufka fellow from Hard Facts I knew I could push the hostility limit. His articles have been a staple of that trashy magazine for years. Anything he got from me would sell, and he knew I wasn’t going to give him the goods. I saved the earth-moving details for myself or journalists who needed a break. Half the time I don’t even know why they interview me. They don’t ask about diseases or infections. Instead, they inquire about my childhood, and they ask about my family’s opinion of my blog. When I hear that stuff, I put on the interviewee boxing gloves and see what I can get the journalist to admit. As soon as I get something juicy out of my interlocutor, I say I don’t feel well and thanks for coming. The interviewers look like a judge denied their parole.

After only a few years of chasing bugs, the sicknesses became burdens. Each fever felt more enervating than the last. My doctor said my kidneys were akin to a 10-year-old Brita filter from taking 9,000 mgs. of ibuprofen every month. Internal statistics like liver enzyme count or cholesterol were abstract in my youth. No longer a child, I woke in the middle of the night with my kidneys beating like hearts and with my liver numb and tingly like a sleeping limb. Most foods and fluids were emetic. Pain shot up and down my spine when I coughed. And not all of my pain was internal. Sores grew on my nose from excessive blowing and rubbing. My voice had the timbre of a garbage disposal. More than once I caught a reflection of myself sitting on the toilet while wearing sunglasses. No matter how cool Ray Bans can make someone feel, they make the shitting man lose whatever pride he had.

And there on my couch I lay, April seventh and on my third fever of the year, like a dying man with his life flashing before his eyes. Only my flashback had been truncated to include the dumbest moments of my life. Here is the time I called my mom a fucker. There is the time I drank mercury from a thermometer. Let’s not ignore my response to getting grounded: smashing my dad’s $3,000 guitar and dumping his antipsychotics in the toilet. And look out, it’s the time I hit my brother in the scrotum after he had surgery to correct his testicular torsion. Perhaps my eulogy will be a string of mistakes chained together. Here lies the king of the idiots.

While I was neck-deep in my self-pity, I heard a shy knock on the door. I didn’t know what time it was, but it felt late. Since I hung sheets over the windows, my internal clock had become unreliable. Getting off the couch took minutes. Going from prone to standing was worse than the trials endured by Odysseus, Hercules, and Oedipus combined. I hoped I would take too long, and the knocker would leave. The feeble knock sounded again. My quadriceps tightened and my hamstrings burned. My palms were too sweaty to steady myself meaningfully. My vision wobbled. Sweat lubricated my nose, making my sunglasses slide a few centimeters too low, thereby exposing my eyes to the stinging light. Another knock. Much louder, harder. I had already made too much noise to pretend I wasn’t home.

I peeked through the eyehole and saw a handsome young man, no older than twenty-five, standing with a sloped back and sunken eyes. He was holding something. I waited until I saw him wipe his nose with it, and I realized it was a handkerchief.

“What do you want?” I asked.

“I’d like to speak with you,” he said, and after a pause added, “sir.”

“What’s with the kerchief?”

“I have a cold, sir. May I come in?”

“Why would I let a sick person in my home?”

“Sir, we both know you’d rather let someone sick in your home.” Well played. I respected his moxie. My eye stayed at the hole while I unlocked the door. He stood upright when he heard the bolt disarm. I opened the door and the sickly boy smiled. I looked him over. He was unassuming, tall but wiry. His long bangs didn’t hide his receding hairline. Above his eyes sat two brows as angular as Nike swooshes. He went too far with the tweezers.

When he entered my apartment, he turned his head to its limit in each direction. He tried to hide his wandering eyes under the guise of a neck stretch.

“Casing the joint?” I asked.

“No, sir. I—”

“Drop the sir shit.”

“No. I’m just looking around. To see if,” he paused, ashamed. “Just seeing if it looked how I thought it would.”

“Does it?”

“No,” he said. “The articles make it sound like a toxic waste dump.”

“You aren’t looking close enough.” We sat in sweat and silence. I plopped my head onto an armrest. My slightest movement renewed his boyish grin. When I blew my nose he tensed, as if he were watching a sex scene with his parents. The boy’s silent gaze annoyed me, and his motivation was still ambiguous. I wanted to pose the question delicately, but in my stupor, I said, “Why are you here?”

“Do you not read your message boards?”

“Message boards?”

“The comments,” he said. “On your website, the discussions are lively. I’m one of the more active users on there. Some of us fans pooled our knowledge and through some sleuthing figured out where you live.” I barely registered what he was saying. Still fixated on the comment section, I realized that was what my sister meant when she called the website interactive.

“What use was that?” I asked. He stared at me. “What use was coming here? What do you want? I’m not feeling well, and I’m not particularly fond of gawking guests.”

“I just wanted to see you in person.”

After I found out Antonio had spent the last of his money on flying from Minnesota to California, I humored him with a night of conversation. I knew my blog had gathered momentum, but I was misguided about its appeal to the public. My readers did not look to me for information or for layman’s explanations of medical mumbo jumbo. Antonio explained that some of them saw me as a novelty act, like the idiots in internet videos who put live bullets in microwaves. Others thought of me as anarchy incarnate, flipping the proverbial bird at the medical establishment.

Antonio and similarly loyal followers diverged from both of those perspectives and had a more, in my eyes, paranoid understanding of my lifestyle. According to Antonio, I had become a paragon of stoicism. He said my neutral tone when writing about my own sickness attracted the Online Stoic Society (OSS). Initially, recreational thinkers enjoyed drawing links between my writing and the works of early stoics, zeroing in on coincidental uses of the same words. I didn’t want to spoil the fun by telling him about the art of translation. He said the discourse had been amateur at best. But Professor Isaac Graham out of San Diego published a paper called, “How to Succeed in Getting Sick without Really Trying: The Stoicism of Germ Chasing.” Professor Graham located specific parallels between my years of illness and the development of western stoicism. He argued that my work unfolded chronologically with the works of Zeno, then Epictetus, then Marcus Aurelius, and so forth, all the way through the transcendentalists and into the twenty-first century.

I read through the essay. At best, it was a hodgepodge of gobbledygook. In my favorite line, he wrote, “His aleatoric schematism of the problematics of the de-acclimatization of the modern subject to the near pornographic exposure to medical stimuli symbolizes the yoking together of the Stoic dictum of nature as source of truth and the self as interpreter; however, paradoxically, it confronts head-on the simultaneous erasure and apotheosis of the ego insofar as the biological sciences wield a guillotine over the Veil of Maya.” I got the sense that he had read everything except my blog.

The essay became dryer and more prolix and more straining to my eyes. It felt as if he had written it in a font size below zero. The reader must sacrifice her vision to glean information. This was not a fair exchange. I rolled up the essay and stuck it in a moldy cup of coffee. Through one cracked eye, I saw Antonio stare in horror.

I closed my eyes, no longer interested in whether the kid was a threat. My mind needed a break from his lunacy. I imagined dancing with Mae West. She was gentle and talked me through the steps. She forgave me when I stepped on her foot. She stepped on my toes and I pretended to get angry and she laughed and gave my shoulder a flirtatious squeeze. I always assumed she would be too forward and intimidating for me, but she was respectful of my reservation. Unlike her onscreen reputation, she had shy tendencies, too. A skilled actor, she could vacillate between coquettish and introverted personas. An artist of the highest order.

Deep in my dreamland, somewhere between my walking the streets of Paris with Ms. West and splitting a cigar with Gertrude Stein, I achieved serenity for the last time. Childish laughter awoke me. Four more boys had arrived sometime in the night. Antonio and the new boys sat on the small loveseat. A tall, blond boy in a suit would not release my dog despite his attempts to squirm free.

“Who the hell are you?” I asked. They laughed. I stood, head throbbing, and smacked blondie in the face. I took my dog from him, and in a raspy voice commanded them to leave. They giggled. Everything I did was met with laughter. They would not speak. Even blondie, who I was certain would turn against me, smiled through a bloody lip and a pink cheek. “Antonio, what the fuck is going on here? Who are they?”

“They are like me. They have come to meet you.”

“Well, thanks for coming out everyone,” I said. “Time to leave. I’d like to start my day.”

“We would love to see what your daily routine looks like,” said Antonio. His comrades agreed.

“I would love to go about my day without an audience.”

I stared at them, channeling every bit of impatience. A knock at the door interrupted me. Antonio stood from the couch. When he refused to sit, I punched him square in the nose with my second and third knuckles. He covered his face, but a pop noise and the pain in my hand told me I had broken his nose. Blood leaked between his fingers and streamed down his wrists onto his clothes. In less than a minute he looked like he had just finished a shift at a slaughterhouse.

Another, harder knock on the door. Indeterminate chatter, then a strange jiggle. Silence again. The lock disarmed and three more boys about Antonio’s age entered the apartment. The boys on the couch did not take their eyes off of me. The three new boys closed the door behind them as if they had entered their own childhood homes. They stared at me with the grins that had become too familiar. My requests registered with them, for they would smile and nod while I ordered them to leave. However, they took no action. Most frustrating of all was how comfortable they were in my apartment. They kicked their feet up on my table, dug through my cabinets, drank my cough syrup. A crew cut in a leather jacket thumbed through the dog-eared pages of my Tim Allen book. A few of them waited by the door to let in any newcomers. I thought of myself as the captain of a ship, one that pirates were overtaking while it was sinking. Sharks circled, and my crew joined the pirates.

Against my orders, new people piled in and made themselves comfortable. Other than a sleeve of saltine crackers, the hoard found nothing of interest. They finished digging through my cabinets, and they stopped what they were doing in unison. I stood near the fireplace watching them. They closed in, forming a half-circle and sitting on the couches and floor. They stared. No one spoke. My slightest motion excited them. I rubbed my eye and they leaned forward as if I were whispering the secrets of the universe.

“What do you want from me?” I asked.

“We want to know what’s next,” a voice said. I was silent. The voice said, “You taught us that feeling equals feeling, symptoms are symptoms, pain is pain. Nothing more.”

“Where did I say this?”

Antonio said, “Your life’s mission.” And everyone repeated, “mission.”

They ignored my words, but they dissected my language. I was speaking to a room of detectives who thought they could get a big break in a case if they found the right clue at the right time. Nothing I said had surface-level meaning, only subtext. A command was a lesson, a sigh was a symbol.

I had to test the limit of my influence. I had to formulate a real strategy for removing this mass. I fetched a knife from the kitchen and held it to the nearest boy’s throat. His eyes widened, but his body obeyed me. The only change in the group was a couple boys’ brandishing of notepads and pens, taking notes on my posture and facial expressions. I cut the boy’s palm. He expressed no signs of stress, but he said, “I understand.” I dragged the knife down the back of his hand and watched the skin split and spread until his first metatarsal appeared through the gash. He peeled open the skin and bared the bones in the back of his hand. The bones became more pronounced when he bent his fingers, appearing robotic in their consistent, linear movements. A young boy interrupted the spectacle, asking, “What is the lesson here, sir?”

“Only that you’re willing to let a stranger cut your hand.”

“You taught us not to fear pain, or fear, or angst.”

“All I do is fear pain,” I said.

“Sir, there are hundreds of instances in which you use the word ‘phlegm’ on your site. We have discussed this in detail during our meetings. You determined for us that phlegm is the primary bodily humor. To be phlegmatic is to live the germ chaser life.”

How do you deprogram a group of folks you didn’t realize you brainwashed? Up until now I couldn’t think of anyone who would take my advice with anything less than 10 grams of salt. Now I had assembled a squadron, anxious and eager, an army of young men willing to listen, willing to experience any amount of pain or anguish I would put them through. But I was the one they looked to, I was the giver of wisdom and learning, I was the one they would protect.

I backed away from the group and held the knife against my throat. As a final experiment, I would see if a human could behead itself. Like a tidal wave, moving at a clip no one thought possible until it tore through a town, the group caved in on me, wresting the knife from my hands and slamming me on the floor before I could hurt myself.

The last image I remember is a tan boot coming down on my face. I closed my eyes and felt the back of my head bounce on the tile floor. I’m not certain if my eyes staying shut was a conscious choice, but I remained blind while the group thrashed me. I could hear the bones in my arms snap and break and bust, until they were sacks of shards and fractures. I had to assume they’d be flaccid bags for the rest of my life, incapable of performing the humblest tasks. Even if they stopped at the arm breaking, I’d spend the rest of life eating steak through a silly straw and peas from a dog bowl, on all fours, fed by a friendly hand that I dare not bite.

I started to think that this imagined future would be better than the past decade of my life. At least I would have companionship. I had a friend whose arms didn’t work, and he adapted. As if they sensed I had achieved about as much peace as a person can while taking a toe to the teeth, the mob lifted me and passed me around above them. They crowd surfed me to my couch and placed me flat on my back. I could barely open my eyes. My face warmed with blood, and my shirt stuck to my chest.

The group backed off and stared. I wasn’t sure if they were checking to see if they mortally damaged me or if they were waiting for new instructions. “Ice,” I said, trying to read anything in the room.

“We can’t,” a voice said.

“You taught us to endure pain. We will not betray you while your wits are absent,” another voice said.

And another voice said, “When you can think clearly you will be grateful.”

Antonio said, “For phlegm is the way.”

“Yes,” I said. “Phlegm. Sit me up.” Two boys pulled me by my armpits into a seated position. “Listen, men,” I said. “The time has come for your newest lesson in the balance of humors. One of you, gather the knives from my kitchen counter.” A pimply stooge gathered eight knives, more than I thought I had. He set them down on the coffee table and looked for my approval. I said, “Men, you have let me down. Your group response to my self-mutilation signals how little you have learned of the humors. You overlook how toxic excess blood is to the mind. I was going to relieve myself of the blood that so weighs me down and disrupts the power of phlegm, for blood is one of phlegm’s three enemies. A few of us will confront bile, black and yellow, in time. For now, this room pulses with a sanguine beat that it cannot afford.” No one moved. When I paused, the air conditioner shut off. I had these sons of bitches propped atop a trapdoor. All I had to do was flip the proper switch and watch them plummet to their obsequious deaths.

“Friends, sickly and feverish, time for the first of our three catharses. Use these knives to purge your bodies of extraneous blood. Cut your femoral arteries and release the imbalance.” Nobody spoke. A bearded boy followed my instructions first, slashing through his jeans into his inner thigh. He handed the knife to a younger boy, who dug it into his leg, removed it, and watched his own blood spill slowly at first, then like a hose relieved of a crimp, he bled as fast as the laws of nature permitted. I assumed the other boys would reconsider cutting themselves after watching the others fall to the floor. I was mistaken, for I had underestimated once again the grasp I held on these boys, how easily I could will them into self-destruction.

After the first two boys collapsed to the floor, the rest of the room participated in the bloodletting. The unspoken agreement was to cut your own leg and hand off the knife. It was a shame that the only effective demand I made to the group was to commit mass suicide.

The floor had become a pool of blood about an inch deep. All of the boys were either dead or unconscious. I heard tentative little footsteps splashing through the gore. I tried to look around, but I was limited to my peripheral vision. The footsteps stopped on the floor in front of me. My dog jumped into my lap, squeezing the air out of my lungs and leaving tiny, bloody pawprints on the remaining white portions of my shirt.

I sat wondering whether I was a murderer. I figured I was at least murderer-adjacent. Perhaps in that case I thought joining in the fun would be best. No need to try and explain what it was that happened in there. No need to sweat under a bright light, telling detectives how a group of paranoid boys discerned a pattern from my dumb blog. I would kill myself once I could conjure the energy. I would roll off the couch and dig a knife into something vital.

But the door burst from its hinges. With the racket from the boys beating me, I should have been surprised the cops didn’t show up earlier. Two burly, browbeaten officers, uniform men, kicked the door in. I assumed they would cite some horseshit law afterward, saying they had every right to break my door down. They looked around at the corpses. One of them let out a you-seeing-this-shit whistle, the kind that lasts a couple of seconds and descends in pitch.

“There he is,” said the whistling cop. The two of them knelt in front of me. “Are you hurt?” one asked.

“Can’t move,” I said. He nodded.

“What happened here?”

“Tough to say.”

After inspecting some of the corpses, the other cop said, “They started without us.” The cops picked up knives from the floor. They knelt in front of me, slashed their thighs, and said, “For the phlegm.”