Winner of the EXTINCTION Essay Contest, selected by Lacy M. Johnson

“This excerpt from “Colluvium” is about gender, trauma, and how violence can make the body feel like an unsafe space — an attempted annihilation that the self might inadvertently repeat while trying to undo the harm it has experienced at the hands of others. This is an unsettling, revealing, and fiercely intelligent essay. I was riveted by this bold new voice.”

Lacy M. Johnson

Excerpt from “Colluvium”

Put a bindweed flower face-down in a bowl of water, sealing it off like a skin.

Let it sit all afternoon, while the earth rolls over the face of the moon, and the moon comes out whole on the other side. Let it sit well into night. Then mix the water with brandy, part for part, and take a few drops of this, and add it to a drinking glass. And swallow it and feel the threads of your history gather and feel the threads of your history streaming together, like beams of light, like old beams of light, all pouring out now through your back.

– –

And anything you say can become a spell. Anything you choose to say.

Open the door.

Open the door.

Open the door and get out of the way.

– –

When the wind stops blowing. You’ll see. When the wind stops blowing, you will understand.

There was a drummer in the room, remember? He was sitting at your feet. And it was his job to be the heart. And the heart has only one job to do: keep on, once it’s chosen to start.

You were in the basement of a house in a bowl the land made, and which glaciers and time marked with stones.

And we are why you went there. The rocks in the earth and that wind. You were calling us home.

– –

Do you shiver more these days? Do you feel somehow bigger than you used to be?

Then you know we are here. Your army of girls. Your sparkling wake, your infantry.

– –

And when you think of someone who liked to make you helpless, who wanted to rust you shut, say: that part of the story is over.

That part of the story is over, and the pendulum starts swinging. That part of the story is over, and someone gets buried in sand. That part of the story is over, and the line gets cut, and you did it. You did it yourself with the scissors. You did it yourself, your two hands.

– –

And when you think of someone who liked to keep you small, remember they will now have to watch you grow huge. And now you are out of reach. And now you’ve rewired the circuitry. And now, they cannot touch you.

– –

“Are you ready,” she asks, “to begin?”

The needle in the inkwell. The needle in your skin, over and over, a pain you are not resisting, over and over until the last word is legible: swim.

And all the while, there is a girl in her first pond in the last of the light. The day and the air and the pond gone gold, and she is under there for a long time, it is where she wants to be. And you see the shape of her as the ink goes in. Body under water, certain as a knife.

– –

This is the lullaby, and this, the toy that plays it. These are the hands that wind the key, this is the house high on the hill, tight as a drum with the sound going through.

This is the face of the girl we were. Look at me.

– –

Walk out into the dusk, out into the magnetic light, where the thrush is throwing its flute-song higher and higher.

We have those where I live, says the girl who is suddenly there.

Oh, yes, you say. I remember.

– –

A satellite girl in a series of satellite years.

Are you here? Are you here?

Of course. I am here. I am heres.

– –

What was it that was written on the first page. Who bore down so hard that the impression of these letters could be read, in deboss, on all of the pages that followed.

What was it that was written. What did the message say.

– –

There are enough of us now to write something else. There are enough of us now to stand on the shore, shaking with cold, head tipped to drain the ocean from our ears.

There are enough of us now to say the smallness was an error, and we are shivering at the edge of the land, all bathed in light and salt, and we are never going back there.

– –

They did not know about the clock you had built and the way it kept time. They did not know it could wind in all directions, and stop for a while while you did the work. They did not hear the second hand between the silences, ticking, or the word it repeated: Mine. Mine. Mine.

– –

Go to the closet and pull the box down from the shelf. Find the rolls of film you finished thirteen years ago. Pry them open in the kitchen. And ruin them with light.

Shake them into ringlets, you can feel the moments leave. All gone grey, these things you do not need.

– –

The shadow of your hair on the sand of the beach. The shadow dripping. The shadow, going dry. The shadow beginning to curl.

– –

It didn’t quite do what they hoped it would do. Everything they tried to break just grew back huge.

We are laughing and our eyes are bright. Now? we ask.

Now.

Like a flashbulb, we blow out the room.

– –

Late in the day, when the sun writes a line of light upon the sea, you can rip apart the bright seam. You can do it easily. You aim the prow of your hands right through the middle, cleaving the water, stitch after stitch.

Close your eyes when the work is done, and watch the memory fade. The glowing after-image.

– –

The new sound is the mirror on the driver’s side, the screws coming loose in their housing, the screws letting go very slowly the longer we drive.

– –

Now look, we say to the arms of what was.

You cannot even wrap yourself around us.

Now look, we say to history: we have given you a name. And that is an insult you cannot survive. You will never be the same.

– –

Say it in the voice of the lichen on the rock.

Say it in the voice of the light through the water.

Say: the truth is slow, but the truth cuts through. I will tell you what I know, and I am not afraid.

– –

It is possible to hold your own hand across time. And then, you will know the feeling from both sides—the reacher and the reached-for, and time is nothing. Time is just a wall, and here is where we built a door.

It is possible that long ago, when you cried out real but silently for help, that the hand that reached back is the hand that is writing this down. This hand, this self.

And so we cannot be stopped. We flash across the face of the earth like the impulse that takes over a flock of seabirds. Out and back across the water, nothing has been spoken, but every single one of us has heard.

– –

And out there on the blue horizon, someone is singing. The song is a tower, a lighthouse, a bell.

She is just beyond the curve of the earth, and you call to her, who are you?

I am here, she says, to hold this song until you learn to sing it for yourself.

It is a song whose end requires beginning again. It is a song that bites its own tail, in a language we can only speak alone.

And what do the words mean, one of us asks. There is only one word. It means no.

Meredith Clark is a poet and writer whose work has received Black Warrior Review’s Nonfiction Prize, and been published in Gigantic Sequins, Berkeley Poetry Review, Phoebe, Poetry Northwest, Denver Quarterly, and elsewhere. Her first book, Lyrebird, is forthcoming from Platypus Press in 2020.

About the contest judge:

Lacy M. Johnson is a Houston-based professor, curator, activist, and is author of the essay collection, The Reckonings, as well as two memoirs, The Other Side and Trespasses. The Other Side, a haunting account of Johnson’s experience of sexual and domestic violence at the hands of her ex-boyfriend, weaves together a richly personal narrative with police reports, psychological evaluations, and neurobiological investigations, provoking both troubling and timely questions about gender roles and the epidemic of violence against women. The Reckonings also draws from Johnson’s personal experience of gender-based violence, as well as from philosophy, art, literature, mythology, anthropology, film, and other fields, to consider how our ideas about justice might be expanded beyond vengeance and retribution to include acts of compassion, patience, mercy, and grace. The Reckonings was named a National Book Critics Circle Award Finalist in Criticism and one of the best books of 2018 by Boston Globe, Electric Literature, Autostraddle, Book Riot, and Refinery 29. The Other Side was named a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in Autobiography, the Dayton Literary Peace Prize, an Edgar Award in Best Fact Crime, and the CLMP Firecracker Award in Nonfiction; it was a Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writer Selection for 2014, and was named one of the best books of 2014 by Kirkus, Library Journal, and the Houston Chronicle. Her work has appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, Paris Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, Tin House, Guernica, Fourth Genre, Creative Nonfiction, Sentence, TriQuarterly, Gulf Coast and elsewhere. She teaches creative nonfiction at Rice University and is the Founding Director of the Houston Flood Museum.

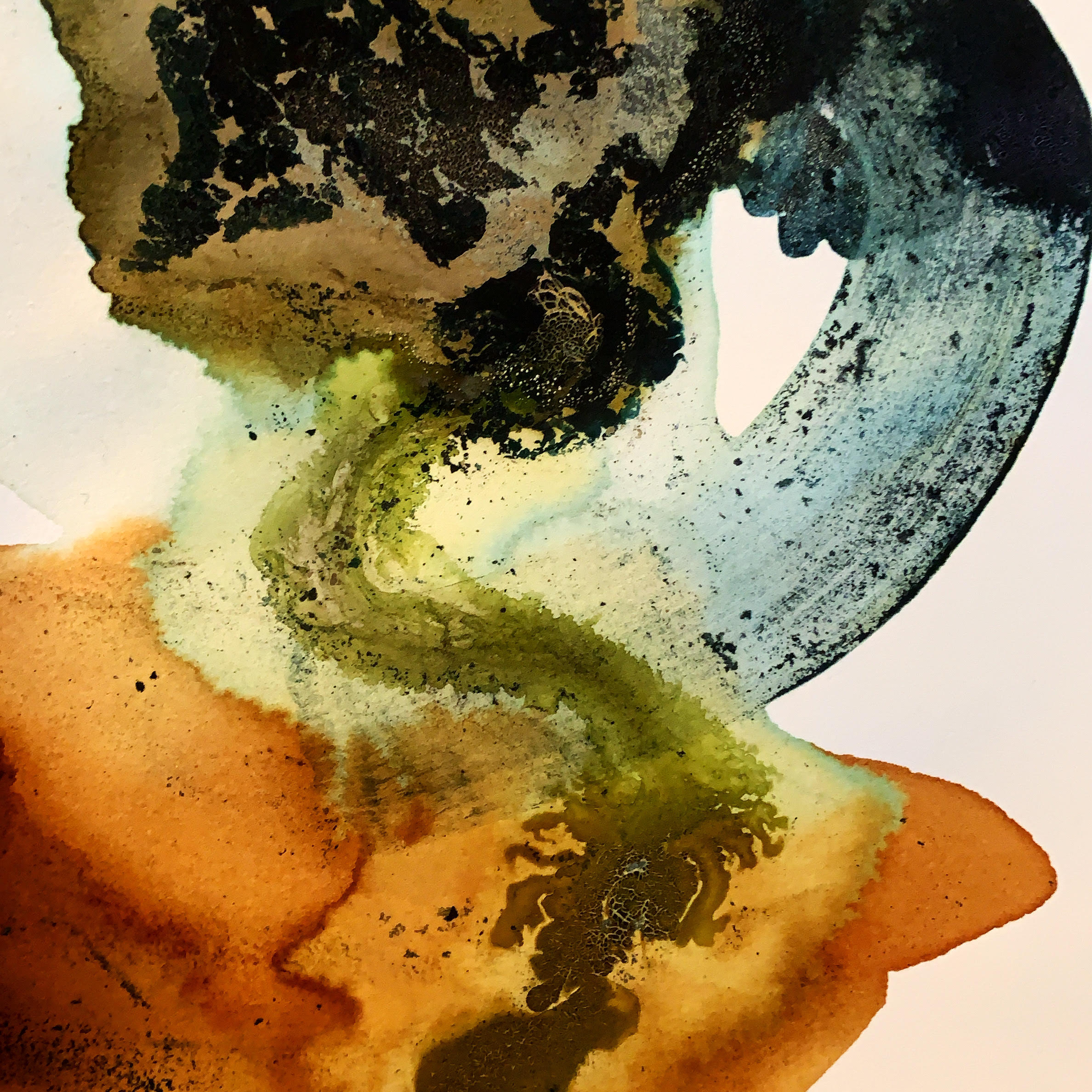

Image: “Rail spike rust, buckthorn sap, copper, thorn ashes, sea water,” by Toronto Ink Company